I am Iris.

Urban legends are not just fiction—

I am the narrator who traces the unspoken truths with you.

- This is an urban-legend style commentary—interpretation, not a scientific verdict.

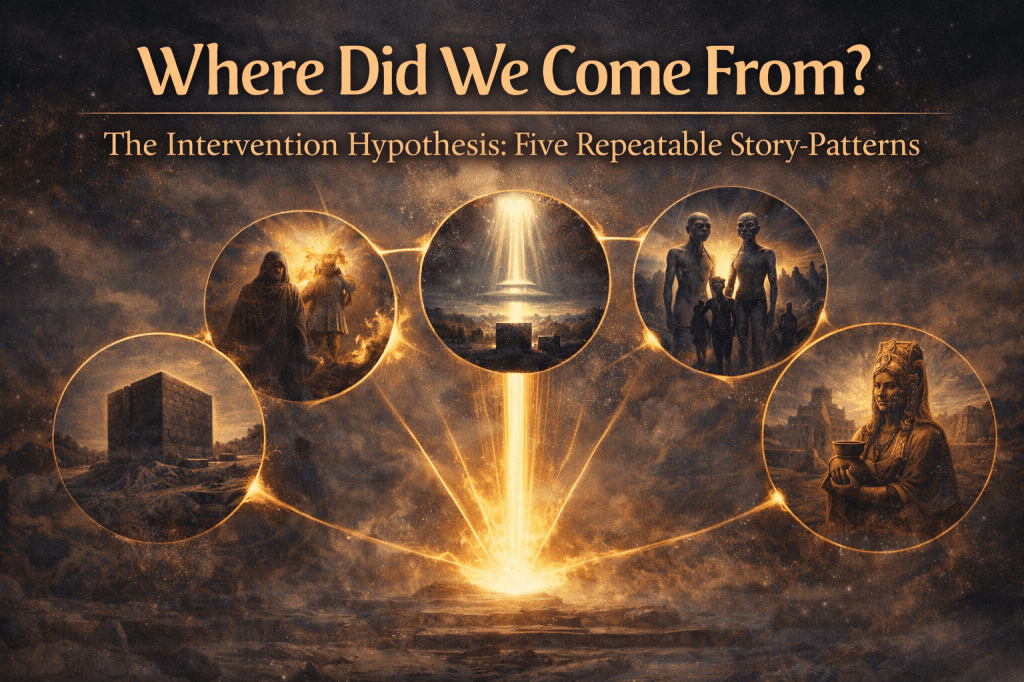

- We map the “intervention hypothesis” into five repeatable story-patterns seen across cultures and eras.

- The goal is clarity: how the narrative works, why it spreads, and what it tries to explain.

Note on Framing

This article is written as urban-legend commentary. It does not claim proof. It examines a recurring narrative structure—how people frame human origins when they suspect an “outside hand.”

Why the Intervention Hypothesis Keeps Returning

When someone says, “Humans arrived too fast,” they rarely mean only bones and dates. They mean the suddenness of mind—language, symbolism, law, music, math, myth. In that emotional space, gradual explanations can feel unsatisfying, even when they are methodical.

So a different model appears: an interruption.

Not necessarily a spaceship—sometimes a teacher, a watcher, a maker, a hidden elite, a celestial order. The names change. The rhythm stays.

Across urban-legend circles, the intervention hypothesis often behaves less like one claim and more like a template. Below are five story-patterns that reappear so consistently that they function like a “grammar” of modern origin-mystery.

Pattern 1: The Leap (Sudden Upgrade)

This pattern begins with a single emotional argument: “The jump is too steep.”

It focuses on moments that feel discontinuous:

- rapid symbolic behavior,

- complex language,

- “civilization appearing,”

- toolmaking sophistication,

- mythic memory that seems older than it should be.

In this pattern, the “gap” is not only in fossils; it is in narrative expectation. The audience senses a before/after boundary, like a cut in a film.

Urban-legend readers often interpret that cut as an upgrade event: something inserted capacity into the human story. Whether framed as genetics, instruction, or suppressed history, the function is the same—explaining why humans appear “too equipped” for the timeline.

Pattern 2: The Teacher (Knowledge Delivery)

The intervention model rarely stops at “we were changed.” It usually adds “we were taught.”

This is where civilizational skills enter the plot:

- agriculture,

- writing,

- astronomy,

- architecture,

- law codes,

- measurement systems.

In many versions, an outside actor does not create humanity from scratch; it delivers knowledge at the moment a society is ready—or vulnerable. The tone is often documentary: lists of “impossible knowledge,” timelines of sudden complexity, stories of “first kings,” “first cities,” “first calendars.”

The teacher pattern is persuasive because it offers a simple bridge between mystery and modernity:

If knowledge arrived from elsewhere, then the speed of civilization becomes explainable.

Pattern 3: The Covenant (Rules, Taboo, and Control)

This pattern introduces rules.

A boundary appears:

- a forbidden tree,

- a restricted fire,

- a sacred mountain,

- a sealed chamber,

- a tablet of laws,

- a name that must not be spoken.

In intervention narratives, taboo is rarely just morality. It becomes a control interface—a way to keep humans within a designed lane. The story implies that the outside actor is not merely generous; it has objectives.

This is also where “obedience” and “punishment” motifs become central. The audience is invited to see origin as governance: humanity is not only born, but managed.

The covenant pattern resonates because it mirrors real life:

rules shape societies, and societies shape people. The story simply moves the origin of those rules one layer upward.

Pattern 4: The Bloodline (Selection and Legitimacy)

Intervention stories often become genealogical. They ask: Who counts as “the line”?

This pattern appears in two forms:

- biological selection (chosen genetics, hybrid lines, engineered traits),

- political selection (chosen kings, divine right, sacred lineage).

The bloodline pattern gives intervention narratives durability because it converts a cosmic mystery into a social structure. Once lineage enters the story, origin becomes hereditary—something inherited, protected, hidden, and fought over.

It also creates a natural villain/hero framework:

- those who “guard the blood,”

- those who “stole the blood,”

- those who “forgot the blood,”

- those who “must awaken.”

Even when literal genetics is not emphasized, legitimacy language often functions as a substitute. A dynasty does not need a lab to become a “chosen line”—it only needs a myth that authorizes it.

Pattern 5: The Archive (Edited Record and Missing Original)

The final pattern is the most modern in tone: the file-system worldview.

Here, myths and ancient records are treated as edited documents—curated outputs of a deeper archive that we no longer possess. The story shifts from “What happened?” to “Who edited it?”

Common motifs:

- lost tablets,

- forbidden books,

- burned libraries,

- censored chapters,

- translation disputes,

- “the original meaning was removed.”

In this pattern, intervention is not only an ancient event; it is an ongoing information war. The outside actor (or its inheritors) is imagined to manage narratives across centuries—selecting what survives, shaping the public memory of origin.

This is persuasive because it matches contemporary reality: we live inside information systems. We know how editing changes truth. So it becomes natural—almost inevitable—to imagine that the origin story itself was edited.

Why These Patterns Feel So Believable

Each pattern solves a specific psychological demand:

- The Leap solves the demand for a clean “before/after.”

- The Teacher solves the demand for rapid civilizational complexity.

- The Covenant solves the demand for power dynamics at the beginning.

- The Bloodline solves the demand for identity, legitimacy, and inheritance.

- The Archive solves the demand for explanation when evidence is fragmentary.

Even if none of these patterns are provable, they are narratively efficient. They turn the origin question into a structure the mind can hold: a mystery with mechanisms, roles, and stakes.

How This Connects Back to the Hub

This is one branch of the broader debate map. For the full framework—how evolution debates, creation narratives, symbols, and intervention claims sit side by side—use the parent hub here:

Where Did We Come From? — Human Origins Debate Map (Hub)

The Clean Takeaway

The intervention hypothesis persists because it behaves like a reusable template. It can attach itself to fossils, myths, kings, symbols, and modern anxieties—then reorganize them into five familiar patterns.

And once a story can reorganize anything into a coherent shape, it stops being “just a claim.”

It becomes a lens.

Next time—another fragment of truth to trace with you. I will return to the story.

Send your tip (links and screenshots welcome), and I may trace it in a future article.

コメントを残す