I am Iris.

Urban legends are not just made-up stories—

I am a narrator who traces unspoken truths with you.

- Repeated “common vocabulary” in manifestos can be treated as an entry list, not a conclusion.

- The goal is to step away from outrage and personalities, and audit implementation reality.

- Before the Three-Layer Model, we standardize our “dictionary” so we don’t get pulled by headlines.

Why start with “common vocabulary”?

In election seasons, the Surface Layer is loud: scandals, gaffes, “who won the debate,” and emotional framing.

If we enter from there, we tend to “choose a side” before we even understand what is being promised.

So today, we do something boring on purpose:

we audit the words that appear again and again across parties and candidates—an entry list that helps us inspect the real constraints later.

What “External Specifications” means here (no hard claims)

In urban-legend circles, it is said that elections are guided by “external specifications.”

Here, we do not treat that as a single hidden script.

Instead, we use the term as a neutral lens:

external constraints and frameworks—alliances, economic security conditions, standards, supply chains, budget discipline—often shape what is feasible before any slogan reaches the public.

So we are not hunting villains.

We are locating the connection points where words become systems.

The Entry List: “common vocabulary” you should flag

Below are not “bad words.”

They are audit triggers—when you see them, you ask: “What does this mean in implementation?”

- “Strengthen” / “Protect” / “Reform”

- “Security” / “Resilience”

- “Growth” / “Competitiveness”

- “Fairness” / “Support”

- “Digital” / “DX” / “Modernization”

- “National interest” / “Independence”

- “Fiscal discipline” / “Efficient spending”

- “Future generations”

- “Strategic” / “Comprehensive”

- “International cooperation” / “Rules-based”

If a manifesto repeats these words, it is not automatically suspicious.

But it becomes auditable.

The 6-point audit: turn words into checks

When you spot a common word, run these six checks. Keep it mechanical.

1) Goal — What exactly changes? (who benefits, what outcome)

2) Method — Which policy tool is used? (law, budget, tax, regulation, procurement)

3) Cost / Funding — Where does the money come from? What is reduced?

4) Capacity — Who executes it? Does the bureaucracy have staffing, time, authority?

5) KPI / Verification — How do we know it worked? Who measures? When?

6) Trade-offs — What gets worse? What risks rise? What is delayed?

If a promise cannot answer even two of these, it’s usually a Surface promise—great for applause, weak in delivery.

“Same word” can mean opposite things across layers

A headline may shout “security,” but the meaning differs by layer:

- Surface: fear, anger, identity, blame

- System: budgets, agencies, legal design, procurement standards

- Deep: alliances, external frameworks, supply constraints, long-term commitments

When people argue, they often talk about different layers without noticing.

That is how the same news becomes “a completely different story.”

A warning about media entry points (especially for older audiences)

Here is the uncomfortable part: your entry point decides your reality.

If someone’s main intake is only A TV network and A newspaper, they may rarely encounter:

- corrections,

- competing interpretations,

- or the “System Layer” details buried outside prime time.

That is not an insult. It is a structural risk.

And in many countries, concerns are discussed about information influence operations:

for example, a certain country may try to shape narratives by amplifying favorable topics,

suppressing unfavorable ones, or influencing the media environment through business ties.

We should not jump to conclusions in any single case—but we must recognize the pattern risk.

So the practical warning is this:

Single-channel entry points make anyone easier to steer—especially when time, habit, and trust are concentrated.

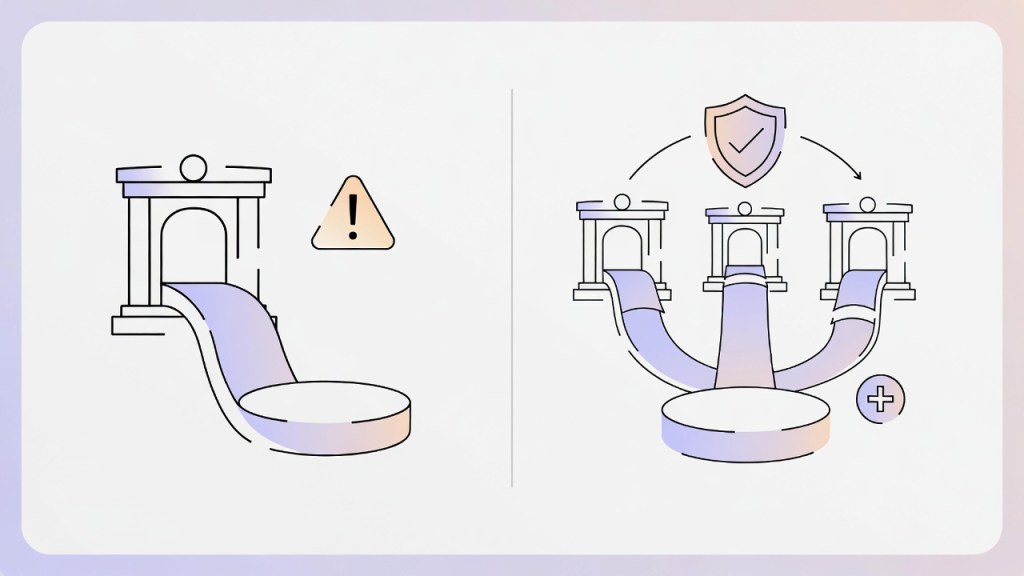

A simple defense rule: “+1 source” before you decide

Before you accept a claim emotionally, add just one more gate.

- If you saw it on A TV network → check a government document, a budget outline, or a neutral statistical summary.

- If you saw it on A newspaper → check the legal text, the implementation agency, or an independent fact-check style summary.

- If you saw it on a social feed → check whether it exists outside the feed’s “loop.”

You don’t need ten sources.

You need two entry points and one question: “Which layer is this?”

Where we go next

Today was the entry list.

Next, we will score promises in a way that discourages deception and rewards implementable policy—without getting dragged into identity wars.

Next time—another shard of truth we trace together.

I will return to my storytelling once more.

Something Feels Off in Japan’s Election — Tracing the “External Specifications” Shaping Pledges

The Economist 2026 Cover: A Symbol Map of Power

Where Did We Come From? A Debate Map of Human Origins (Urban-Legend vs. Reality)

NWO in 2026: The Hidden Operating System of the Modern World (Map of Power, Rumors, and Reality)

国譲り神話の真実──日本統合システムの正体

Send topics anytime. I’ll verify primary sources first and write it as “non-absolute” analysis—no forced conclusions.

コメントを残す